A SEMI-FICTIONAL MANCHESTER

WRITTEN BY Hayley Flynn

READING TIME: 12 minutes

Imagining the city’s most fantastic plans.

Back in 2012 I acted as a guest curator for Northern Spirit. Over the course of a week I wrote about Manchester Hippodrome, Sunlight House and the Picc-Vic underground transport system that never materialised, and tied these visions and memories together by imagining them all occurring at one time, under the fictional remit of architect Joseph Sunlight as head of the city (now Cottonopolis) planning department. I’ve republished these articles, as one, below.

Cottonopolis: A Skyline Reimagined

My family are predominantly from Liverpool, and so it’s safe to assume I’m the black sheep of the family in my adoration of Manchester. I love it because I feel like I’ve made it my own. It’s a city where it’s very easy to do that and to carve yourself a place where you slot in and feel at home regardless of your roots. It’s also a challenging city to love because you have to work at it. There’s nothing immediate about it, it’s small yet spread out, it’s unremarkable in many ways, and you certainly don’t get that breath-taking moment of flinging open your hotel window and gazing down on an urban paradise – its not an easy city for a visitor to love.

Manchester was my blank canvas when I first came here and it remained that way for several years, just a corner of the canvas was filled in and it was rudimentary and pencil drawn. Then I realised that I hadn’t approached the city like I do all other cities; as a tourist – always asking questions about its history, its art, exploring the streets and getting lost in its dead-ends. I did this and my canvas became florid in its detail. I still explore like this everyday because there’s no reason, in any city, for that curiosity to ever wane.

I’ve adopted Manchester as a home and so it saddens me when a building I love is at threat, with that in mind I’ve looked at what Manchester could have been had these threats never reared their heads. What we’ve lost and what we almost had.

Over the years there has always been a kind of marvellous futuristic machinery at work behind the scenes of some of the major buildings. In the late 19th century Manchester Hydraulics Systems supplied this brand new source of power to the air conditioning of John Rylands Library (in itself a ground breaking concept at the time), the safety curtains of the Opera House, the organ of the Cathedral, and the clock of the Town Hall.

The Palace Hotel on Oxford Road used this hydraulic power in a fashion not dissimilar to something you’d expect to see in the Coen Brothers’ ‘Hudsucker Proxy’. They installed a series of tubes in what was then the Refuge Assurance Building, and inside of leather-bound capsules they would seal notes before dropping them into the suction system and transporting them to another part of the building.

Sunlight House on Quay Street is perhaps something of a silent star in amongst all of these landmarks and ground-breakers. It’s a grand building on an otherwise bland street, it’s not a building whose name is instantly recognised nor is the purpose of it clear to the everyday passer-by, but it’s this building that’s inspired me to look at Manchester as it could have been.

There are lots of ways in which the skyline of Manchester could be re-imagined but I’m going to look at a handful of possibilities: of proposals that were never approved, and outstanding buildings that were demolished.

Cottonopolis, Manchester’s moniker during the industrial revolution, already conjures images of a Metropolis (be it Superman’s or Fritz Lang’s) but when you think of it realistically – a city born of cotton mills, well it doesn’t hold that same excitement, not the excitement that you’d experience in a city dominated by a behemoth of a skyscraper that’s made entirely of imposing white Portland stone. A skyscraper that looks down on a giant hippodrome that was built to be flooded so that it could ensure the most spectacular of shows. And how about the secret foundations of the city and the empty pockets of space underground that were intended for something a little more bustling.

Here we look at these eventualities and re-imagine the skyline of Manchester; Cottonopolis.

And it’s Sunlight House where the outline of a new city begins…

Sunlight in the Rain

Joseph Sunlight was born in Russia but came to Manchester with his family in pursuit of a fortune wrapped in cotton, and Joseph grew up to become a prolific architect, soon becoming one of the city’s wealthiest citizens. When he died in 1979 he was the city’s biggest taxpayer. By proxy we owe a lot to Joseph Sunlight, but it’s likely that most residents don’t know who he is.

Joseph Sunlight had a vision for Manchester, one that’s evident in his art deco creation Sunlight House, on Quay Street. The white Portland stone building stands proud on a street of unremarkable neighbours.

In 1932, at the time of being built, Sunlight House was the tallest building in the city and the first skyscraper in the North of England. Erected during the ’30s depression, when the city seemed to be set in aspic, when nothing changed, and the machinery of the industrial boom had rusted itself a place in the present. This great white hope of a building wasn’t a municipal location but merely the office of Sunlight’s property business. What’s so appealing about this place is how it’s something of an anomaly in Sunlight’s catalogue. He designed houses, and he built the elegant Sunlight House simply as a place to continue his practice of house design. This office – optimism in Portland stone – was intelligent and inspired, but in Sunlight’s mind it wasn’t complete.

The awe inspiring design stands at 14 storeys, but the architect had intended for its original reach to be more like 30. Walk down Quay Street sometime, head away from the city, in the direction of the Irwell, and take a look at this marvellous chunk of stone. It’s so permanent seeming, as if a naturally occurring monolith. Now, look up to its beautiful row of windows high above the street, see if you can spot the art deco eagles on each corner. Now consider the height and double it. Just imagine what an impact something of such size and stature could have had on Manchester.

Inside of Sunlight House a unique vacuum system was in operation that made the task of maintaining the building more manageable. A similar one can be found in Liverpool’s Royal Court Theatre in which a central vacuum is plugged into by a hose via periodic holes in the skirting boards of the building. The cleaners only need carry a light, flexible hose with them and not an entire vacuuming contraption. Nothing at Sunlight House was about showing off, yet in its competence it did just that.

From all accounts is seems as though Joseph Sunlight was something of an eccentric. In in his lunch hour, in place of an attendant he would operate the high-speed lifts himself, and his wish was to be buried in a mausoleum on the roof of the building. Sadly, stories dictate that this was a wish Sunlight went to his death bed believing would be honoured, but it was never to be. Perhaps, then, it’s Joseph who is the ghost said to haunt the building – ghosting the lift shafts, traversing the floors in search of a burial place never built.

A proposal for an extension to Sunlight House was reported in The Manchester Eyewitness on 15 August 1948, and it read:

‘Manchester Skyscraper Proposed! Plans for a Manchester skyscraper, an extension to Sunlight House, Quay Street, are to be presented to the Draft Schemes Sub-Committee. It will be twice the height of the present building, and will be built between Sunlight House and the Opera House. It will be surmounted with a large clock tower. The £1m, 35-storey, 360ft building has been designed by Mr Joseph Sunlight.’

Sunlight took his inspiration from the solid, ornate skyscrapers that dominated the Chicago skyline. Few buildings adopted this style, but, if they had, Manchester might have been a very different city. If we’d had the bravery back in the ’40s to go ahead with Sunlight’s vision, if we could alter history and reverse what is perhaps one of the city’s worst planning decisions of the time, then we might have an ultimately more gothic and intriguing city; a city unrecognisable as British, but instead a city straight off the pages of a noir fantasy – solid and white, as if furniture draped in Manchester cotton.

Horse Powered

Previously we looked at Sunlight House, its creator Joseph Sunlight, and his plans to extend his Quay Street building with the addition of a 40-storey clock tower. Now we continue to imagine the city with Sunlight at the helm of the city’s planning department, and what that might mean for Manchester’s skyline today.

In Sunlight’s Manchester it’s not all about sculpting the skyline into the future but also retaining the landmarks that fit in with this: his noir-novel of a city.

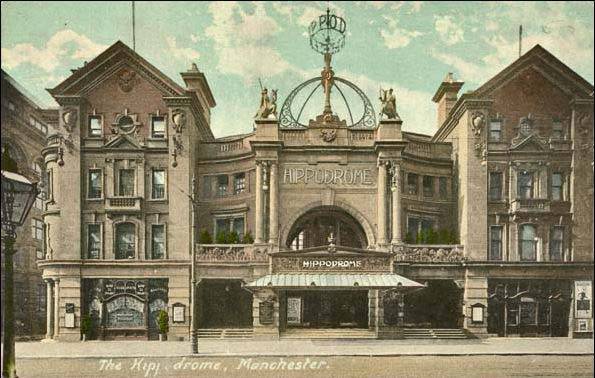

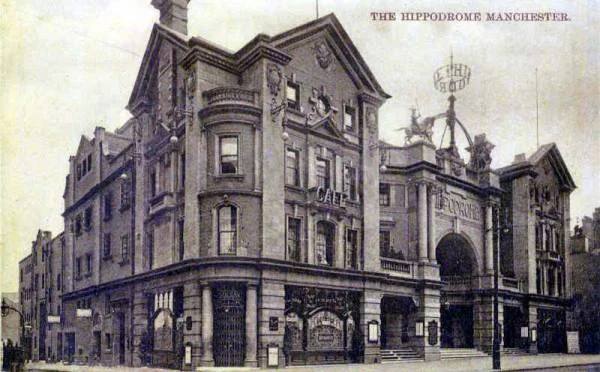

From these imaginary floors of the Sunlight House clock tower, in a room besides the giant clock face, Joseph Sunlight regards his city and gazes down the curve of Quay Street until it meets with the start of Oxford Street. Just beyond the curve that heads Southbound along the cultural and educational mile, a sign mounted high above a building catches his eye. It’s a circular sign, flanked by sculpted horses, and it seems to float independently of the building. It glistens and rotates and advertises the site below as Manchester’s Hippodrome.

Manchester Hippodrome and neighbouring Picturehouse (now McDonalds)

Manchester Hippodrome

image Old UK Photos

The building was always theatrical, not only in function but in form, and the 54 feet wide proscenium arch, the very bones of the building, was moveable – it was a theatre with a sliding roof. Built to house circus performances with room for 100 horses, a variety theatre and, later, to screen films, the hippodrome didn’t limit itself to the confines of a regular theatre and housed a giant tank that could hold 70,000 gallons of water purpose built for ‘water spectaculars’.

"A Foot to a Fathom of Water at the Touch of a Lever!"

The Hippodrome was an ornate but sturdy type of a building that fit perfectly into Sunlight’s world with its decorative but timeless style. It looked every bit at home in Sunlight’s Manchester of the future, the stony-white Chicago-inspired skyline with streets lined by great modern tributes to architecture, and inspirational updates to the relics of industrial wealth beyond just the mill conversions of today’s city.

In Cottonopolis – Sunlight’s Manchester – the Hippodrome remains. It morphs into a future version of itself and the circular sign comes to life; lights up; rotates. His Manchester is not purely new vision, but it’s a place bound together with the iconic structures of the past.

Manchester Hippodrome existed in Manchester between 1904 and 1935, when it then was rebuilt and became the Gaumont theatre, later Rotters Nightclub until it ended its life in demolition in 1990 to eventually be resurrected as a multi-storey car park.

Above and Beneath

The Cottonopolis City Planning Department (formerly the City of Manchester) is nestled in amongst the rooftop offices of Sunlight House, besides the Clock Face. Joseph Sunlight, head of the department, takes a seat in the window and looks out onto the city.

Between the skyscrapers are a series of elevated walkways that connect one building to another. In the Manchester 1945 Plan these walkways were put forward as a Le Corbusier inspired method of segregating vehicles and people – and they were approved in the Oxford Road district. You can see a few which remain to this day as well as the ghosts of old connections between the first floors of neighbouring buildings.

The Royal Northern College of Music has almost removed all traces of its own walkway now but if you look across to the Business School you can clearly see the space where the connecting walkway once attached to it. There are examples all over Manchester today of elevated thinking, though not always complementing each other. Imagine for a moment all of these walkways spanning Oxford Road, taking pedestrians from site to site without the bother of traffic, then think of that greying arm draped around the South of the city – Mancunian Way. Where does that fit in to all of this? A motorway in the heart of the city that runs parallel to the walkways and at that same first floor height.

Another example of this sky-high future can be spotted over at the Mercure Hotel, formerly the Piccadilly Hotel. If you take a look at the building which sits on a podium above the street-level shops, you’ll notice that the original entrance is found up there on the first floor too. Bernard Sunley built this hotel with the vehicular future in mind, reasoning that everyone would arrive by car by the ’60s and no doubt taking inspiration from that lofty Mancunian Way. Sunley didn’t provide a pedestrian way into the building, the only way in was by the concrete car ramp.

These roads aren’t prevalent in Cottonopolis but they do exist, cars are still necessary in Sunlight’s future, but it’s the public transport that makes the city so successful. Sometime after this fanatical road building, a plan was proposed for Manchester’s own underground network. The Picc-Vic line was actually some way to being approved and when the Arndale Centre was built the foundations were made with this tube network in mind, so there’s a cavern underneath the Arndale, right below Topshop, and it’s a ghost station for a line that was never to be.

The tube network would eventually stretch right out to the suburbs of the city and stations were planned at Royal Exchange and St Peters, with a rather lovely reimagining of Albert Square that saw the cobbles outside the Town Hall replaced with a landscaped forecourt. In Cottonopolis, Sunlight saw to it that these plans were approved and by 1973 an extensive underground of high speed trains delivered the public across their rainy city.

Albert Square landscaped for the Picc-Vic line

Whilst researching another article I uncovered multiple letters in the archives that Joseph Sunlight had written in to The Guardian over the years regarding planned city developments, I discovered these some months after publishing this series of articles and it was lovely to uncover them and see how my fictional account of the man as city planner spills over into reality in these archived letters. I’ve published one of his letters in my City Tower article, where he suggests that instead of building Piccadilly Plaza we instead build a civic or cultural centre for the city.

Mr Sunlight, I salute you.